Think of a fog desert as a place where rain is rare, yet moisture still sneaks in—quietly, almost like a secret delivery. Instead of storms, you get a steady rhythm of coastal fog, a cool marine layer, and tiny droplets that land on rock, plants, and soil as usable water. These landscapes look minimal at first glance, but the real story is in the moisture systems that keep life going when the sky refuses to spill a drop.

- Quick Snapshot

- What Makes a Fog Desert

- The Moisture Machines Behind the Mist

- Cold Water, Warm Air

- The “Lid” in the Sky

- How Water Moves Without Rain

- Life That Drinks the Air

- Common Adaptations You’ll See

- Fog Oases and Local Sweet Spots

- Fog Harvesting in Plain Terms

- What Makes a Fog Collector Work Well

- How to Read Fog Patterns Like a Pro

- Frequently Asked Questions

Quick Snapshot

If you want a fast handle on a fog desert, focus on how it gets moisture, not how often it rains. Here’s the vibe:

- Rainfall is low, but fog can be frequent and surprisingly reliable.

- Cold ocean water nearby often helps build a stable marine layer.

- Water arrives as droplets, dew, and fog drip (also called occult precipitation).

- Life is tuned to timing: mornings, evenings, and wind shifts matter more than seasons.

What Makes a Fog Desert

A fog desert is an arid region where water arrives mostly through fog and low cloud, not through regular rainfall. The key is repetition: a lot of small wet moments instead of a few big storms. Over time, those micro-deliveries of moisture become a real ecological budget—enough to support lichens, hardy plants, and animals that know exactly when to show up.

Many fog deserts sit along coasts where cool seas meet warmer air. That temperature mismatch helps build advection fog—fog that forms when humid air moves over a cooler surface and chills to its dew point. Add steady winds and a stable low cloud deck, and you get a fog belt that can stretch inland for long distances (in some places, over 100 kilometers). That’s not a drizzle, but it’s not nothing either.

The Moisture Machines Behind the Mist

Cold Water, Warm Air

Upwelling and cool sea surfaces help keep near-shore air chilled. When warmer, moist air slides over that cooler surface, it condenses into fog droplets. This is one reason coastal fog is so common in certain dry shorelines: the ocean acts like a cold plate that turns invisible vapor into visible mist.

The “Lid” in the Sky

Fog deserts often sit under a temperature inversion: a layer where warmer air rests above cooler air. It’s like putting a lid on a pot—vertical mixing slows down, and the marine layer stays shallow and stable. That stability is great for persistent low cloud, even when the wider region remains very dry.

Topography then takes over. Coastal hills, ridges, and valleys can funnel the moist layer inland, especially during daily wind cycles. In some landscapes, the fog doesn’t just roll in; it threads through valleys like smoke, settles into basins at night, and then thins out as the day warms. That daily loop is a big part of how moisture reaches places that seem far from the shoreline.

How Water Moves Without Rain

Fog deserts are powered by “horizontal” water capture. Droplets in fog stick to surfaces—plant leaves, spines, stones, even spiderwebs—then merge into larger drops and fall. That drip is often called fog drip or occult precipitation. It may look tiny, but when it happens often, it can wet the topsoil, feed microbes, and keep seeds waiting for just the right moment.

Dew matters too. On clear nights, surfaces can radiate heat away and cool below the dew point, letting water condense directly onto rocks and plants. Dew is usually thinner than fog water, but it’s incredibly local—one boulder might be damp while the sand beside it stays bone-dry. This is where microcliamte details become everything.

| Moisture Input | Where It Comes From | How It Reaches Ground | Who Uses It Most |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fog | Marine layer droplets | Direct contact, surface wetting | Lichens, small plants, insects |

| Fog Drip | Fog intercepted by obstacles | Droplets merge, then drip down | Soils, shrubs, root zones |

| Dew | Nighttime condensation | Forms on cool surfaces | Surface microbes, seeds, small animals |

| Low Cloud Shading | Persistent stratocumulus | Reduces heat and evaporation | Everything that benefits from cooler days |

Life That Drinks the Air

In a fog desert, survival is less about “finding water” and more about catching it. Some plants pull moisture straight from the air using leaf hairs, waxy surfaces, or sponge-like textures that hold droplets long enough to absorb. Others rely on fog drip collecting on their own stems and spines, turning their body into a miniature water tower.

Animals get clever too. Many are tuned to the hours when fog is thickest, becoming active when surfaces are wet and stepping back when the sun dries things out. Some insects can collect droplets on their bodies, guiding condensation toward their mouthparts. It’s a tiny-scale plumbing system, and it works because the mist returns again and again.

Fog in a desert is like a quiet banker—small deposits, made often, and always on schedule.

Common Adaptations You’ll See

- Fog-harvesting surfaces: leaf hairs, textured skins, or waxy coatings that grab droplets.

- Minimal leaf area: less surface to lose water, more control over evaporation.

- Low, ground-hugging growth: closer to the coolest air, where fog lingers longer.

- Timing strategies: blooming, feeding, and moving during the damp window when mist is present.

Fog Oases and Local Sweet Spots

Fog deserts aren’t evenly “foggy.” They’re patchy. A ridge can scrape cloud like a comb, while a nearby slope stays clear. A boulder field can stay cooler at dawn, holding condensation longer than open sand. Over time, these patterns create fog oases—pockets where plants and insects cluster because moisture shows up more often.

In some coastal deserts, seasonal fog can support short-lived green bursts on hillsides and in sheltered folds of terrain. These spots often act like living “islands” surrounded by bare ground. If you’re trying to understand a fog desert, zoom in. The big map tells you it’s dry; the small map tells you where life keeps finding its next sip.

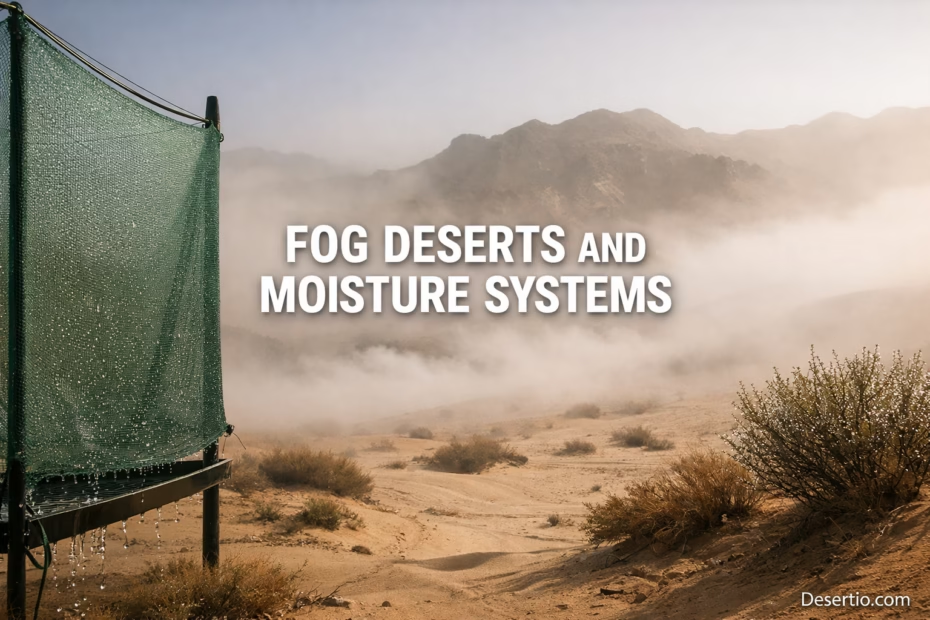

Fog Harvesting in Plain Terms

Fog harvesting is a human-friendly version of what desert plants already do: place a surface in the path of moving fog, let droplets stick, then guide the water into a clean collection channel. The classic setup uses mesh nets positioned where wind-driven fog is common. As droplets collide with the mesh, they merge and drip downward—simple physics, no magic, just surface area and the right airflow.

What Makes a Fog Collector Work Well

- Location: a spot with frequent fog and steady breezes, not dead-calm air.

- Orientation: facing the main fog-bearing wind so droplets hit the mesh head-on.

- Mesh choice: materials and weaves that catch droplets without clogging too fast.

- Drainage path: a clean gutter or channel so collected water doesn’t re-evaporate on the surface.

- Maintenance: keeping the surface clear so droplet capture stays consistent.

Friendly note: Fog collectors don’t “make” water. They capture moisture already present in the air, so performance rises and falls with fog frequency and wind flow.

How to Read Fog Patterns Like a Pro

If you’re studying a fog desert, pay attention to when fog shows up and where it sticks around. Fog often thickens during cooler hours, then thins as sunlight warms the ground. Watch for low, flat stratocumulus offshore, steady onshore flow, and a visible “fog line” where mist stops and clear air begins. That boundary can shift day to day like a slow tide.

Terrain clues help too. Saddles, passes, and valley mouths can act as fog doorways. Rocky surfaces may stay cooler at dawn and hold condensation longer than loose sand. And if you notice lichens, delicate crusts, or fog-fed plants, you’re probably standing inside a repeatable moisture corridor rather than a random damp spot.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is a fog desert still a desert? Yes. A fog desert is defined by low rainfall and high aridity, even if fog moisture makes certain pockets feel surprisingly alive.

Does fog replace rain completely? Not always. In many places, fog is the most dependable moisture source, while occasional rain still happens—just not often enough to run the whole system.

What is “occult precipitation”? It’s hidden-style precipitation: fog droplets intercepted by surfaces that later drip to the ground as fog drip, often missed by normal rain gauges.

Why do fog deserts often hug coasts? Coasts can combine cool sea surfaces, steady winds, and a stable marine layer, creating repeatable fog formation even when inland air stays dry.