Desert landscapes may look empty at first glance, but if you zoom in far enough, you’ll find a buzzing invisible world. Every grain of sand, every crust on the soil surface can be home to tiny, stubborn life forms we call microbes. These desert microbes quietly shape climate, soil, even the way deserts might hint at life on other planets.

- What Exactly Is Desert Microbial Life?

- Extreme Challenges Microbes Face in Deserts

- Major stresses

- Microbial responses

- Hidden Micro-Habitats: Where Do Desert Microbes Live?

- Hot vs. Cold Deserts: Microbes in Both Worlds

- Key Groups in Desert Microbial Communities

- Why Desert Microbes Matter for the Whole Ecosystem

- Desert Microbes and the Search for Life on Other Planets

- Human Impacts on Desert Microbial Life

- How Scientists Study Microbial Life in Deserts

When we talk about microbial life in deserts, we mean bacteria, archaea, fungi, algae and viruses surviving where water is rare, temperatures swing wildly, and sunlight can be brutal. It sounds impossible, but these organisms have evolved tricks that let them hang on — or “pause” life — until the enviroment gives them a tiny window to grow again.

What Exactly Is Desert Microbial Life?

Desert microbial life is basically the full community of microscopic organisms living in desert soils, rocks, dust, and rare water pockets. Together, these communities form what scientists call the desert microbiome, a kind of invisible ecosystem that supports plants, animals, and nutrient cycles. Even in the driest deserts like the Atacama or the Arabian deserts, microbes are there, just hidden and often sleeping.

- Bacteria & cyanobacteria – photosynthetic pioneers that build soil crusts and fix nitrogen.

- Archaea – champions of extreme heat, salt and dryness.

- Fungi – decomposers and partners of plant roots (mycorrhizae).

- Algae & microalgae – tiny “plants” that live in crusts, rocks or temporary pools.

- Viruses – microscopic “genetic shufflers” influencing which microbes thrive.

Key idea: if you see a “barren” desert, remember there’s an entire microbial city hidden in the sand, rocks and dust, running quiet processes that keep the ecosystem alive.

Extreme Challenges Microbes Face in Deserts

To understand desert microbes, it helps to look at what they’re up against. Conditions in places like the Sahara, Gobi, or Sonoran Desert can flip between freezing nights and scorching days. Water might appear only a few hours per year. On top of that, there’s intense UV radiation and often salty or nutrient-poor soils.

Major stresses

- Desiccation (extreme dryness)

- Heat & cold shocks

- UV light from strong sun

- High salt in some soils and lakes

- Nutrient-poor conditions

Microbial responses

- Forming spores or dormant cells

- Producing sugary protective gels (EPS)

- Making pigments that act like sunblock

- Hiding in shaded micro-habitats

- Repairing DNA quickly when damage occurs

Many desert microorganisms spend most of their time in a kind of “pause mode”. They shut down metabolism, reduce water inside their cells, and wait. When a short rain, fog event, or even morning dew arrives, they “wake up,” grow fast, and then slow down again. This stop-and-go lifestyle is one of the most important strategies in desert microbiology.

Hidden Micro-Habitats: Where Do Desert Microbes Live?

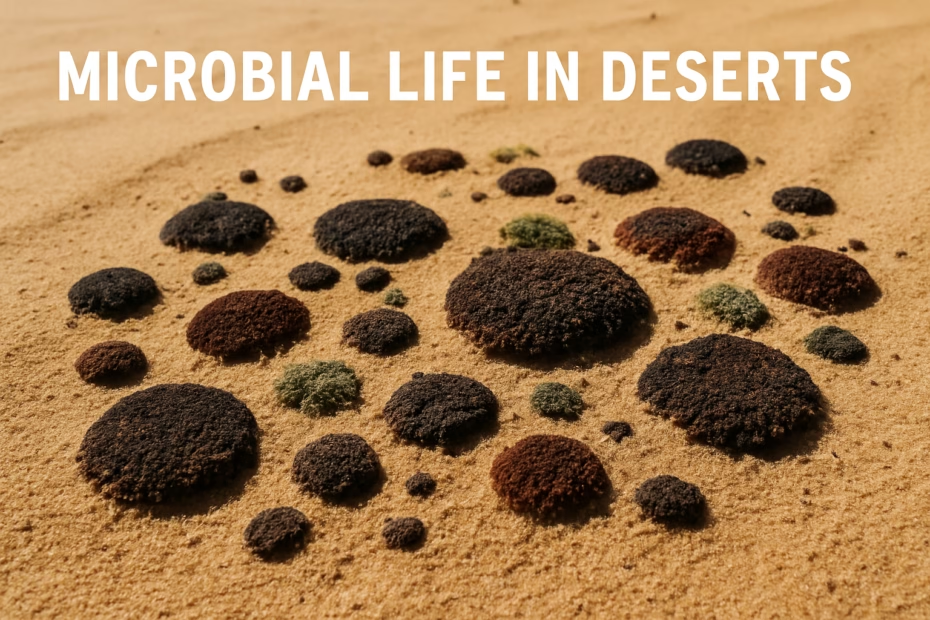

Microbes in deserts rarely sit fully exposed on the surface. They prefer tiny micro-habitats that offer a little more shade, moisture, or protection. The result is a patchy mosaic of microbial hotspots across the landscape, from thin soil crusts to translucent rocks.

| Micro-habitat | Typical microbes | Main advantage | Example deserts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological soil crusts | Cyanobacteria, fungi, lichens, algae | Bind soil, trap moisture, fix nitrogen | Colorado Plateau, Negev, Australian deserts |

| Hypoliths (under rocks) | Cyanobacteria, bacteria | Shaded, stable micro-climate | Namib, Atacama, Antarctic Dry Valleys |

| Endoliths (inside rocks) | Algae, fungi, bacteria | Protection from UV & temperature swings | Sahara, deserts with sandstone or limestone |

| Salty soils & playas | Halophilic archaea & bacteria | High salt reduces competitors | Central Asian deserts, playas in North America |

| Ephemeral water pools | Algae, cyanobacteria, heterotrophic bacteria | Short bursts of intense growth | Wadis, desert streams after rain |

One of the most striking features in many drylands is the dark, sometimes bumpy layer on the soil surface. This is a biological soil crust, or “biocrust,” built by cyanobacteria, lichens, fungi and algae. Biocrusts stabilize sand, reduce erosion, and store carbon and nitrogen — all thanks to communities of microscopic life working together.

Hot vs. Cold Deserts: Microbes in Both Worlds

We often imagine deserts as hot, but cold deserts like the Antarctic Dry Valleys or parts of the Gobi are just as extreme. In these places, water is locked as ice most of the time, and temperatures stay low. Yet microbes still live under rocks, in thin films of liquid water in summer, and even inside permafrost.

In hot deserts like the Sahara or Arabian Peninsula, the challenge is a mix of intense heat, dryness, and strong sunlight. In cold deserts, the main stress is freeze–thaw cycles and long periods of darkness or low light. But in both cases, microbes use similar tools: pigments for UV protection, anti-freeze molecules, and clever ways to hold onto tiny amounts of water.

Quick takeaway: whether the sand is boiling hot or the ground is frozen, desert microbes find tiny refuges where life can hang on.

Key Groups in Desert Microbial Communities

Certain groups show up again and again in desert microbiomes around the world. Knowing who they are helps you understand what they’re doing in the ecosystem.

- Cyanobacteria: photosynthetic microbes that build soil crusts, fix nitrogen, and trap dust and organic matter. They’re often the first colonizers on bare rock or sand.

- Actinobacteria: common in dry soils, able to break down complex organic material and produce spores that survive harsh conditions.

- Archaea: especially important in salty or very hot sites; they can use unusual energy sources and tolerate extreme stress.

- Fungi: from decomposers in the soil to fungal partners in lichens; they help move nutrients and connect to plant roots.

- Microalgae and green algae: often living within biocrusts or inside rocks, contributing to carbon fixation.

These microbial guilds don’t work alone. They form complex networks, sharing nutrients and shaping each other’s survival. A cyanobacterium that fixes nitrogen, for example, supports nearby fungi and other bacteria, which in turn help build stable soil and recycle organic matter.

Why Desert Microbes Matter for the Whole Ecosystem

It’s easy to overlook desert microbial communities, but they support many visible parts of the ecosystem. Without microbes, even hardy desert plants and animals would struggle much more.

- Soil stability: biocrusts bind particles, reduce dust storms, and limit erosion by wind and water.

- Carbon cycling: photosynthetic microbes fix CO₂, while others decompose organic matter, slowly returning nutrients to the soil.

- Nitrogen input: nitrogen-fixing bacteria and cyanobacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen into forms plants can use.

- Water retention: microbial gels (EPS) help soil hold onto moisture just a little longer after rain or dew.

- Plant support: mycorrhizal fungi and rhizosphere bacteria help desert plants access nutrients and cope with stress.

In short, microbes are the quiet engineers of desert ecosystems. They build the foundation that lets shrubs, grasses and even cacti establish and survive in places that would otherwise be almost lifeless.

Desert Microbes and the Search for Life on Other Planets

Many scientists use Earth’s deserts as natural laboratories for astrobiology. Hyper-arid deserts like the Atacama or the Antarctic Dry Valleys are some of the best analogs we have for Mars-like conditions: very little liquid water, high radiation, and large temperature swings.

The fact that microbial life can survive inside rocks or under thin soil layers in these places suggests that, if life ever existed on Mars, it might have used similar protected niches. Understanding how desert microbes repair DNA, manage water, and persist in dormancy helps guide where and how we search for life beyond Earth.

Astrobiology insight: if microbes can persist in the driest corners of our deserts, simple life might be more robust — and more widespread in the universe — than it first appears.

Human Impacts on Desert Microbial Life

Despite their toughness, desert microbial communities are surprisingly easy to damage. A single vehicle track or a few footsteps off-trail can crush biological soil crusts that took decades to form. Once broken, these crusts may need many years to recover, and in the meantime erosion and dust storms can increase.

On a larger scale, climate change and land use are altering rainfall patterns, temperatures and vegetation cover. Overgrazing, agriculture expansion, and urban growth push desert boundaries and disrupt the delicate balance of the desert microbiome. Losing these microbial layers can mean less soil fertility, more dust in the air, and reduced resilience of the whole ecosystem.

Practical tip for visitors: when exploring deserts, stay on marked trails and avoid driving across open crusted surfaces. That thin dark layer under your boots is a living microbial community, not just dirt.

How Scientists Study Microbial Life in Deserts

Because desert microbes are tiny and often dormant, they’re not easy to study. Researchers combine classic fieldwork with advanced molecular tools to figure out who is there and what they’re doing.

- Soil and rock sampling: collecting material from biocrusts, rock surfaces, or under stones.

- Microscopy: using light or electron microscopes to spot cell structures and biofilms.

- DNA sequencing: identifying species and community structure using genetic markers.

- Metagenomics & metatranscriptomics: studying all genes or active genes in a sample to reveal functions.

- Field experiments: testing how microbes respond to added water, shade, heat, or nutrients.

These methods show that desert microbiomes are often more diverse than expected, with many lineages still poorly known. Every new study can reveal unfamiliar genetic pathways for stress resistance, pigments, or nutrient use — knowledge that might one day inspire new technologies or bio-based solutions.

Big picture: by decoding the strategies of desert microorganisms, scientists learn not only how these harsh ecosystems work, but also how life in general can adapt to the edge of what’s possible.