Desert herbivores look like a contradiction at first glance: plant-eaters living in places that seem almost plant-less. Yet deserts aren’t empty; they’re simply tight-fisted with water and generous with sunlight. In that bargain, herbivores become the quiet pros—built to turn thorny leaves, dry seeds, and salty shrubs into steady life.

- Desert Herbivores and the Rules of Survival

- What Counts as a Desert Herbivore

- The Desert Menu: Seeds, Leaves, and Salt

- Common Plant Foods

- How “Dry” Food Still Helps

- Water Without Drinking: Clever Physiology

- Heat Management: Living Between Fire and Shade

- Small Herbivores: Big Kidneys and Night Shifts

- Seed Specialists

- Leaf and Stem Feeders

- Large Herbivores: Moving Pantries on Hooves

- Mostly Herbivorous Reptiles and Insects

- Regional Spotlights: Who Eats Plants Where

- How Herbivores Shape Desert Landscapes

- Seed Dispersal

- Selective Feeding

- Seasonal Rhythm: When the Desert Turns Green

- Why Desert Herbivores Matter to the Bigger Food Web

- Common Myths That Don’t Hold Up

Desert Herbivores and the Rules of Survival

In deserts, the main challenge isn’t just heat; it’s water economics. Every bite, breath, and step has a cost, so desert herbivores follow a simple logic: save water, avoid overheating, and make plants pay off. Think of them as living accountants in fur, feathers, or scales—balancing energy and moisture with precision isn’t optional, it’s everything.

One important note: “Herbivore” in a desert often means mostly plant-based, not “only leaves, all the time.” Some species may occasionally nibble minerals, chew dry bones for calcium, or take tiny bits of other nutrients when plants are scarce—still, their core strategy is turning vegetation into survival in a landscape where green can be seasonal and shy.

What Counts as a Desert Herbivore

A desert herbivore is any animal that gets most of its calories from plants or plant parts in arid landscapes—leaves, stems, flowers, seeds, fruit, bark, or even dried plant litter. In practice, desert herbivores fall into a few helpful categories, each with its own signature tools.

- Browsers eat shrubs and tree leaves (often thorny or chemical-rich) and rely on selective feeding to avoid overload.

- Grazers focus on grasses and low plants when they appear, often after rain, using timing as their superpower.

- Granivores specialize in seeds—compact “dry food” that can still yield water through metabolism; small rodents are famous for this seed-to-water trick.

- Opportunistic plant-eaters shift between leaves, seeds, and succulents depending on season, tracking the desert’s brief “green windows” with remarkable awareness.

The Desert Menu: Seeds, Leaves, and Salt

Desert plants don’t give themselves away cheaply. Many are spiny, bitter, waxy, or salty—natural defenses that protect precious tissues from being eaten. Desert herbivores respond with precision feeding: choosing parts of a plant, not the whole plant, and often eating in short bursts to spread out chemical load.

Common Plant Foods

- Ephemeral herbs and wildflowers that appear after rain, offering fresh moisture.

- Salt-tolerant shrubs that store minerals; many herbivores have ways to handle salty mouthfuls without wasting too much water.

- Acacia-like browse and other woody leaves, often eaten carefully around thorns with nimble lips.

- Seed caches and fallen pods that stay edible long after green fades, acting like the desert’s pantry shelf.

How “Dry” Food Still Helps

Even dry seeds and leaves can support life because digestion and metabolism release metabolic water. When fats and carbohydrates are broken down, water is produced inside the body—like a tiny, steady internal drip. It’s not a fountain, but in deserts, small wins add up.

Some herbivores also prefer plants that hold moisture in tissues—succulents and fleshy leaves—then pair that with efficient kidneys that conserve every drop. It’s a two-part deal: drink through food, then keep it.

Water Without Drinking: Clever Physiology

Many desert herbivores can go long stretches with little or no liquid water because their bodies are built to recover and recycle. This isn’t magic. It’s anatomy doing quiet, relentless work—like a sponge that never stops squeezing.

- Concentrated urine helps dump waste while saving water; desert mammals often have kidneys tuned for maximum conservation.

- Dry feces reduce water loss, especially in animals that feed on dry browse or seeds.

- Nasal water recovery in some mammals helps reclaim moisture from exhaled air, turning each breath into a mini recycling loop.

- Flexible body temperature in certain large herbivores can reduce sweating, saving water during the hottest hours.

Heat Management: Living Between Fire and Shade

Heat is a desert’s loudest feature, but herbivores often handle it with behavior first, physiology second. Many species shift activity to cooler hours, use shade like a second home, and treat burrows or wind-sheltered hollows as natural air-conditioning. It’s less “brave endurance” and more smart scheduling.

- Early morning feeding when plants are cool and the air is calmer, often with short, efficient meals.

- Midday sheltering to avoid peak heat; small herbivores may retreat underground where temperatures are far steadier.

- Late afternoon browsing as shade lengthens and wind picks up, easing heat load without extra water loss.

- Night activity for many rodents and some larger mammals, using darkness as a temperature drop you can count on.

Body design helps too. Large ears can shed heat; pale coats reflect sunlight; and long legs can lift the body slightly above scorching ground. Even posture matters—standing to catch breeze, resting on cooler surfaces, and minimizing movement when the sun is at its sharpest.

Small Herbivores: Big Kidneys and Night Shifts

Small desert herbivores—especially seed-eating rodents and desert rabbits—often win by being invisible when the day is cruel. Their world is a map of burrows, shadow lines, and seed patches. The headline feature is their water discipline: they can produce extremely concentrated urine and lose very little moisture in droppings, a tight seal on precious fluids.

Seed Specialists

Seed-heavy diets are common because seeds store energy compactly. Many rodents also cache seeds, turning scattered opportunities into a reliable food bank. That behavior isn’t just “cute”; it’s risk management in a landscape that can change overnight. The payoff is steady fuel and metabolic water that comes from digestion.

Leaf and Stem Feeders

Desert hares and rabbits often browse on fresh shoots when available, then shift to tougher plants as seasons dry. Their long ears can work like radiators, releasing heat into cooler evening air. Picture them as living satellite dishes tuned to one signal: staying cool without sweating.

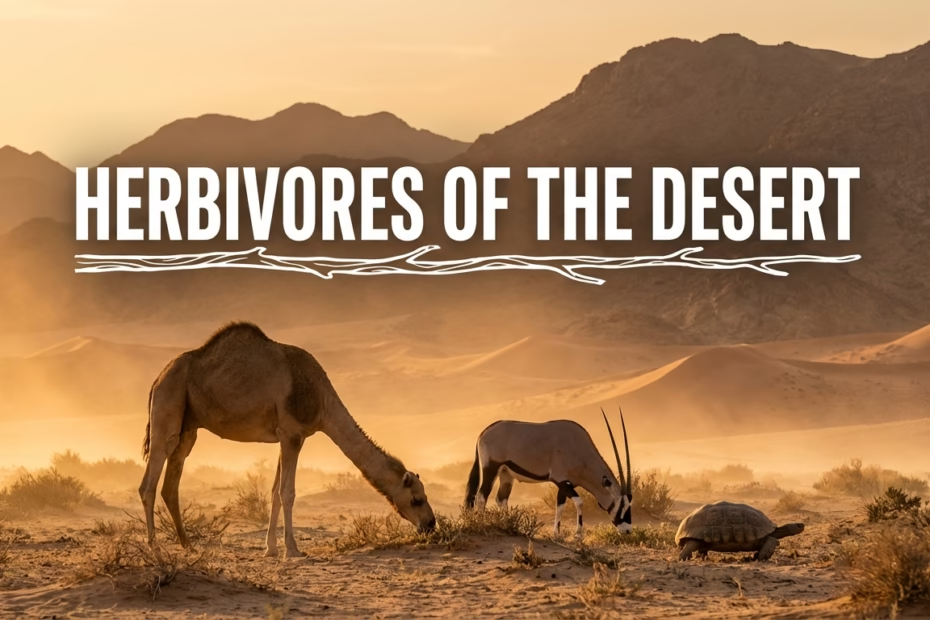

Large Herbivores: Moving Pantries on Hooves

Large desert herbivores—camels, oryx, gazelles, wild asses, and other hoofed plant-eaters—solve scarcity with mobility and efficiency. Their bodies can travel far between forage patches, and many can handle tough, thorny, or salty plants that other animals avoid. In a way, they carry the desert’s food map in memory.

A key advantage is digestive design. Ruminants (like many antelopes) use fermentation to break down fibrous plants, extracting energy from leaves that would be almost useless to many animals. Hindgut fermenters (such as some equids) can process large volumes quickly. Different machinery, same goal: make hard plants worthwhile without burning water.

| Herbivore | Typical Desert Regions | Main Plant Foods | Water Strategy | Heat Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dromedary Camel | North Africa, Arabian Deserts | Dry shrubs, tough browse, salty plants | Handles long dry stretches; uses efficient rehydration | Reduces water loss; uses shade and timing |

| Arabian Oryx | Arabian Peninsula | Grasses after rain, roots, shrubs | Can meet needs from forage when conditions allow | May allow body temperature to rise to cut sweating, a water-saving trade |

| Addax | Sahara and Adjacent Arid Zones | Desert grasses, leaves, hardy herbs | Often relies on moisture in plants | Resting and movement timing reduce exposure |

| Kangaroo Rat | North American Deserts | Seeds and seed pods | Gets water largely from food and metabolism; very concentrated urine | Nocturnal activity; burrows buffer heat |

| Desert Tortoise | Southwestern North America | Spring annuals, grasses, flowers | Uses seasonal moisture; stores water internally | Burrows and shade limit overheating, a slow-and-steady approach |

| Goitered Gazelle | Central Asia and Gobi Margins | Shrubs, grasses, seasonal herbs | Flexible diet helps track moisture-rich plants | Active in cooler hours; uses open terrain airflow |

Mostly Herbivorous Reptiles and Insects

Not all desert herbivores are mammals. Some reptiles lean heavily plantward—desert tortoises are a strong example, often focusing on seasonal greens when they appear. Insects can also be major plant consumers, trimming leaves, harvesting seeds, and turning plant matter into food for the wider ecosystem. This small-scale grazing is easy to miss, yet it can shape which plants dominate after rain. It’s like a tiny lawnmower fleet working the desert floor.

Regional Spotlights: Who Eats Plants Where

Deserts aren’t one uniform biome. A “desert herbivore” in one region may look completely different in another because the menu changes—saltbush here, thorn scrub there, spring annuals somewhere else. Below are a few well-known patterns that show how place shapes plant-eaters, and how herbivores match the rhythm of local rainfall and vegetation. The desert writes the script; animals learn the lines with precision.

Sahara and Sahel Fringe

Across North Africa’s arid zones, herbivores often center on hardy shrubs and short-lived grasses that appear after rain. Antelopes and gazelles are commonly associated with open desert and semi-desert habitats, using movement and selective browsing to stay fed. Many species in these landscapes are tuned to brief green seasons and long dry stretches.

Arabian Deserts

In the Arabian Peninsula’s desert ecosystems, plant-eaters often rely on shrubs, hardy grasses, and seasonal growth after rain. Large herbivores may travel between forage patches, while smaller species time feeding to cooler hours. The common thread is water efficiency—getting moisture from plants and losing as little as possible through sweating or waste. Here, survival feels like a long game.

North American Deserts

Sonoran, Mojave, and Chihuahuan landscapes support a rich mix of herbivores: seed specialists, browsing mammals, and plant-eating reptiles. Seasonal wildflowers can trigger bursts of feeding activity, especially for species that depend on fresh greens. Burrows, shade, and night life are common themes—using the desert’s daily temperature swing like a built-in thermostat.

Central Asian and Gobi Deserts

In cold deserts and semi-desert steppe edges, herbivores often face both heat and winter chill. Many rely on shrubs, tough grasses, and seasonal herbs, shifting diets as conditions change. Mobility matters—tracking forage across wide open distances—while thick coats and flexible behavior help across seasons. It’s desert living with a temperature twist.

Australian Arid Zones

Australia’s dry interior supports iconic large plant-eaters like red kangaroos and other grazing and browsing species adapted to variable rainfall. When rain arrives, plant growth can surge, and herbivores respond quickly—feeding, breeding, and building condition while the window is open. Then the system tightens again, and the focus shifts back to efficiency.

How Herbivores Shape Desert Landscapes

Herbivores don’t just survive in deserts; they organize them. By grazing, browsing, and moving seeds, they influence which plants spread, which stay rare, and how nutrients cycle. In deserts, nutrients can be patchy—so droppings, trampling, and seed dispersal create “hotspots” where plants can do better the next time rain arrives. It’s a quiet kind of engineering, like rearranging furniture in a room that only gets lit for a few minutes each year. Small actions, big ecological ripple.

Seed Dispersal

Many desert plants hitch rides in fur, hooves, or digestive systems. When herbivores move, seeds move too—often landing with a bonus of natural fertilizer. That pairing can improve the odds of germination when conditions finally line up. It’s the desert’s version of delivery service.

Selective Feeding

By focusing on certain plants or plant parts, herbivores can reduce dominant growth and give other species a chance. This can maintain variety in desert vegetation, especially where bursts of growth follow rain. In the long run, that helps deserts stay diverse instead of turning into a single-note landscape. The effect is subtle, but real.

Seasonal Rhythm: When the Desert Turns Green

Most deserts run on pulses. After rain, annual plants can appear quickly, flowers open, and seeds set in a rush. Herbivores respond with their own surge—feeding more, gaining weight, and often timing reproduction so young arrive when plants are most available. Then the landscape dries, and the system shifts into maintenance mode: travel, careful feeding, and lean-season strategies. It’s less a straight line and more a heartbeat.

- Rain pulse: fresh greens and flowers increase moisture-rich forage, making hydration easier.

- Seed set: granivores benefit as plants convert short-lived growth into durable food.

- Dry season: shrubs, pods, and tough browse dominate; herbivores lean on efficiency and timing.

- Recovery: when conditions improve again, bodies and populations rebound with surprising speed.

Why Desert Herbivores Matter to the Bigger Food Web

Plant-eaters are the bridge between sunlight captured by plants and the rest of the animal community. Their bodies store energy, their movement spreads nutrients, and their feeding choices shape vegetation patterns. Even when deserts look quiet, herbivores keep the system running—turning sparse plant growth into life that can support many other species. That role is simple to say, harder to replace, and central to how deserts work.

Common Myths That Don’t Hold Up

Deserts inspire dramatic stories, so a few myths stick around. One is that deserts have “no food,” which ignores the seasonal explosion of plants and the steady presence of hardy shrubs. Another is that herbivores simply “tough it out” through heat, when most are actually masters of avoidance—using shade, timing, and microhabitats like a careful strategy game. The real story is more interesting anyway: deserts are challenging, not empty, and herbivores are specialists, not miracles.