Rain shadow deserts happen when a mountain barrier acts like a giant weather filter, squeezing out moisture on one side and leaving the other side thirsty. If you’ve ever wondered why a green slope can sit surprisingly close to an arid landscape, the rain shadow effect is usually the answer.

- What Makes A Desert A Rain Shadow Desert

- The Three Ingredients

- Why It Feels “Extra Dry”

- The Rain Shadow Effect In Plain Words

- Windward Vs Leeward: A Quick Picture

- Orographic Lift Without The Headache

- Where Rain Shadow Deserts Show Up

- Well-Known Examples

- Not Always “Hot Sand”

- Weather Patterns You Can Expect

- A Small Travel-Smart Note

- Plants, Soils, And Survival Strategies

- How To Identify A Rain Shadow Landscape

- Why Rain Shadow Deserts Matter In Daily Life

- Common Myths That Trip People Up

- Quick Glossary For Rain Shadow Deserts

What Makes A Desert A Rain Shadow Desert

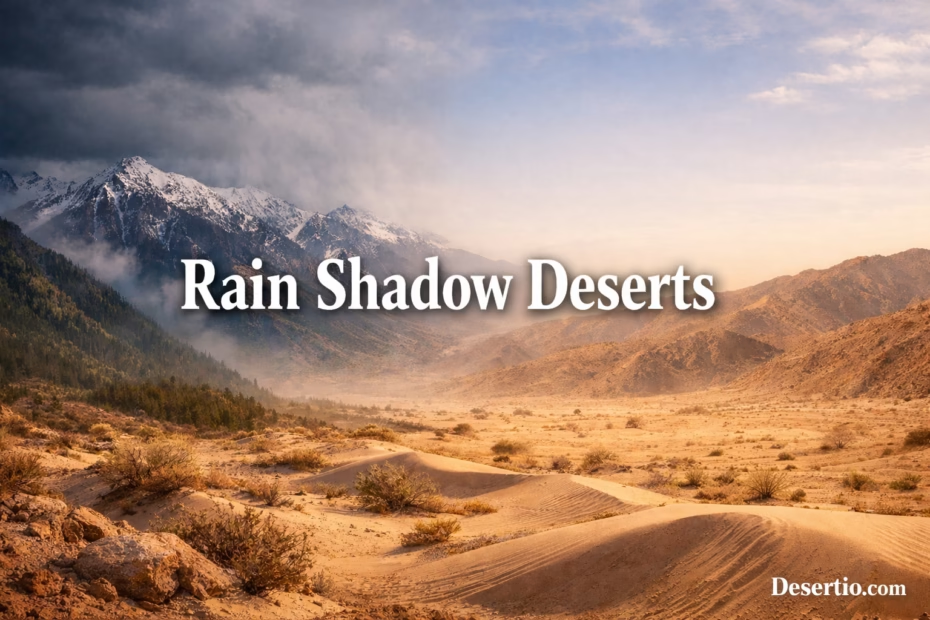

A rain shadow desert isn’t defined by sand dunes or heat alone. It’s defined by position: it sits on the leeward side of a mountain range, where air is descending and drying out. The key idea is simple: wet air rises, drops rain, then the leftover air comes down warmer and drier. That downwind zone becomes a low-rain belt.

The Three Ingredients

- Moisture source nearby (often an ocean, big lake, or very humid lowlands) with evaporation.

- Prevailing winds that push that moisture toward the mountains, keeping the moist pipeline active.

- A mountain range tall enough to force orographic lift and trigger rain on the windward side.

Why It Feels “Extra Dry”

On the leeward side, the air is already wrung out. As it sinks, it warms and its relative humidity drops fast. The sky can look polished for days, and clouds often break apart like cotton pulled too thin. That’s the rain shadow signature in action.

The Rain Shadow Effect In Plain Words

Picture a mountain as a giant sponge in the path of a wet breeze. The air climbs the windward slope, cools, and the moisture condenses. Then the air slips over the crest and drops down the other side, warming up like a hair dryer aimed at the valley. That warming is why the leeward side often turns into a dry corridor with thin rainfall.

- Step 1: Moist air moves inland and meets a mountain wall.

- Step 2: Air is forced upward (that’s orographic lift) and cools.

- Step 3: Clouds form, and the windward side gets most of the rain.

- Step 4: The now-drier air crosses the ridge and descends, warming up as it compresses.

- Step 5: Warm, sinking air lowers humidity, so the leeward side stays rain-scarce.

Mountains don’t “steal” rain so much as spend it early, leaving the downwind side with a smaller budget.

Windward Vs Leeward: A Quick Picture

Rain shadow deserts make more sense when you compare the two sides. The windward slope is where air rises and cools; the leeward slope is where air sinks and dries. That split can shape vegetation, soil moisture, and even the feel of the daylight. It’s like stepping from a misty kitchen into a warm pantry—same building, different vibe.

| Feature | Windward Side | Leeward Side (Rain Shadow) |

|---|---|---|

| Air Movement | Rising, expanding, cooling | Sinking, compressing, warming |

| Clouds | More frequent, thicker, stacked | Fewer, thinner, broken |

| Rain/Snow | Higher totals, more regular | Lower totals, patchy events |

| Plants | Denser cover, deeper greens | Spacing, drought-smart species |

| Soils | More leaching, more organic matter | More salts and crusts in places, thin horizons |

Orographic Lift Without The Headache

Orographic lift is just a fancy label for “air being pushed uphill.” As air rises, pressure drops, and the air expands. Expansion cools it, which helps water vapor condense into droplets. That’s why windward slopes often get cloud build-up and steady precipitation. The moment the air crests the range, it starts descending, warming up, and teh clouds build less easily. That’s the rain shadow switch flipping.

In many ranges, you’ll also hear about warm downslope winds—names change by region, but the feel is similar. These winds can arrive as dry bursts that clear the sky fast, nudging a place toward aridity. It’s not magic; it’s air pressure and temperature doing their quiet work.

Where Rain Shadow Deserts Show Up

You’ll find rain shadow deserts on multiple continents, usually tucked behind major mountain chains. Some are classic “interior” deserts with big seasonal swings, while others lean cooler because of latitude or altitude. What ties them together is the same downwind dryness and the same mountain-driven moisture squeeze.

Well-Known Examples

- Great Basin Desert — shaped in part by the Sierra Nevada rain shadow, with basin-and-range contrasts.

- Patagonian Desert — strongly influenced by the Andes rain shadow, with wide open steppe.

- Gobi Desert — linked to broad highlands and mountain barriers that limit moisture reaching the interior.

- Taklamakan Region — framed by major ranges that promote leeward dryness and isolation from moist air.

Not Always “Hot Sand”

Some rain shadow deserts are cold or high-elevation. Snow can fall in winter, and summer days can still feel sharp at night. The “desert” label is about low precipitation, not about being tropical. Think of a quiet, dry air that keeps water from lingering.

Weather Patterns You Can Expect

Rain shadow deserts often run on a rhythm of clear mornings, bright afternoons, and rapid cooling after sunset. With fewer clouds acting like a blanket, heat escapes quickly at night. That’s why you can get big day-night swings even when daytime feels warm. The air itself can feel crisp—like it’s been filtered.

- Precipitation: Usually light and irregular, often arriving in brief pulses rather than long wet spells, with strong local variation.

- Wind: Downslope winds can be dry and gusty, especially near passes, with dust-ready afternoons.

- Clouds: Thin, fast-moving, and sometimes dramatic near the ridge line, while the basin stays wide-open.

A Small Travel-Smart Note

If you’re planning time in a rain shadow desert, the practical trick is to respect dry air. You can feel fine while losing moisture fast. Light layers help with temperature swings, and simple sun protection goes a long way under clear skies.

Plants, Soils, And Survival Strategies

Life in a rain shadow desert doesn’t “fight” the climate—it negotiates with it. Plants often keep leaves small, waxy, or seasonal, and roots may spread wide to catch quick moisture. You’ll notice spacing between shrubs, like nature is giving each one its own tiny water account. In wetter years, wildflowers can pop up fast, turning a muted palette into a short-lived fireworks show.

Soils can be thin, stony, or crusted in places. Because rain is limited, minerals may stay near the surface instead of washing deeper. That can create salty patches or pale, chalky areas. Where streams come off mountains, you’ll often see alluvial fans—spreading wedges of gravel and sand that act like natural funnels for rare runoff.

How To Identify A Rain Shadow Landscape

You don’t need instruments to spot a rain shadow desert. You can usually read it in the shape of the land and the way plants are arranged. Look for the “two faces” of a range: one side looks lush or at least greener, while the other side looks open and dry. It’s like a mountain wearing two different coats.

- Sharp vegetation change: greener slopes upwind, then scrub and bare ground downwind with clear boundaries.

- Cloud “pile-up” near peaks: clouds cling to ridges while the basin stays blue and sunlit.

- Dry valleys with windy afternoons: a common feel in many leeward corridors, with dust-prone surfaces.

- Stream behavior: channels that are dry most of the year, then briefly active after storms, creating fan-shaped deposits.

Why Rain Shadow Deserts Matter In Daily Life

Even if you never step into a rain shadow desert, the pattern affects where towns grow, where crops thrive, and how water is stored. Windward slopes can hold more forests and reservoirs, while leeward basins may rely on careful water planning. It’s the same storm system, just split into two very different water stories.

This split also creates microclimates. Drive across a range and you might pass from cool, damp air into warm, dry air in a short time. That makes rain shadows a great real-world lesson in how terrain shapes weather. Mountains are not just scenery—they’re climate sculptors with a steady hand.

Common Myths That Trip People Up

Rain shadow deserts come with a few stubborn misunderstandings. Clearing these up helps you read maps and landscapes better, and it keeps expectations realistic when you’re exploring leeward country. Think of these myths as little mirages—pretty from far away, less helpful up close.

- Myth: “Deserts are always hot.” Reality: a desert can be cool or cold; the key is low precipitation, not temperature.

- Myth: “Mountains block all rain.” Reality: they shift where rain falls, concentrating it upwind and leaving a drier zone downwind.

- Myth: “Rain shadows create only sand dunes.” Reality: many rain shadow deserts are rocky, shrubby, or grassy steppe with subtle textures.

- Myth: “One storm fixes the dryness.” Reality: the pattern is persistent because winds and terrain keep repeating the same drying setup.

Quick Glossary For Rain Shadow Deserts

- Rain Shadow Effect: the drying pattern created on the leeward side of mountains after moisture falls on the windward side.

- Windward: the side facing incoming winds, where air tends to rise and cool.

- Leeward: the downwind side, where air sinks and dries.

- Orographic Lift: air being forced upward by terrain, often leading to cloud formation.

- Relative Humidity: how “full” the air is with moisture at a given temperature; warming air lowers it, making conditions feel drier.