Predators are the desert’s quiet architects. When water is scarce and shade is precious, hunters don’t just “eat”—they shape movement, timing, and even the way landscapes feel alive. A dune field at noon can look empty, then come evening it turns into a living map of tracks, scents, and listening ears. If you want to understand any desert—hot or cold—follow the predators’ rules.

- Why Desert Predators Matter

- What Counts As A “Predator” In A Desert

- Core Desert Predators

- Desert “Weapons” That Are Not Weapons

- Deserts Are More Than Sand

- Predator Groups You’ll Meet Across The World’s Deserts

- Mammalian Hunters

- Birds Of Prey And Night Hunters

- Reptiles That Hunt With Patience

- Arthropod Predators In The “Small But Mighty” Category

- How Desert Predators Hunt When Every Calorie Counts

- Senses That Beat Heat And Distance

- Heat Detection

- Sound Mapping

- Scent And Chemical Clues

- Heat And Water: The Hidden Side Of Predation

- A Simple Way To Think About Desert Hunting

- Predator Roles In The Desert Food Web

- Seasonal Shifts: When The Desert Changes The Rules

- Predators As Desert Engineers

- Burrows And Shelters

- Nutrient Hotspots

- Behavior Shaping

- Places Where Desert Predators Thrive

- Respectful Encounters With Desert Predators

Why Desert Predators Matter

In deserts, food arrives in bursts: a good rainfall, a brief bloom, a surge of insects, a spike in rodents. Predators turn those bursts into a stable ecosystem by moving energy up the food chain and preventing any one prey group from taking over. It’s a bit like a conductor keeping tempo—mostly invisible, totally essential. That’s the desert rhythm in action.

- They balance populations of small mammals, lizards, and insects that can multiply fast when conditions are right.

- They recycle nutrients through leftovers and scat, which fertilize thin desert soils.

- They build “activity zones”—around burrows, cliffs, washes, and oases—where many species meet.

- They reveal the desert’s health: a diverse predator community usually means a functioning food web.

What Counts As A “Predator” In A Desert

“Predator” isn’t a single role; it’s a spectrum. In deserts, many animals switch between hunting, scavenging, and opportunistic feeding depending on season and temperature. The common thread is simple: they gain calories by actively capturing other animals, often using speed, stealth, or specialized tools.

Core Desert Predators

- Apex hunters that sit near the top of local food webs (some big cats, large raptors).

- Mid-sized hunters that thrive on flexibility (foxes, coyotes, wildcats, monitor lizards).

- Micro-predators that control insects and small reptiles (scorpions, spiders, small snakes).

Desert “Weapons” That Are Not Weapons

Think of these as nature’s toolkit—no drama, just design. A heat-sensing pit, a silent wing, a sand-ready gait—each one is a solution to hunting in a place that punishes wasted effort.

- Stealth (camouflage, quiet movement, patient waiting)

- Precision (fast strikes, accurate pounces, aerial dives)

- Efficiency (short bursts of power instead of long chases)

Deserts Are More Than Sand

Predators live in deserts made of dunes, yes—but also gravel plains, salt flats, rocky plateaus, and cold deserts where winter bites hard. That variety changes hunting styles. Open flats reward sharp eyesight and speed. Rock piles and wadis favor ambush and short strikes. In cold deserts, predators must manage both heat loss and heat gain across the same year.

The desert is like a huge, quiet library—predators are the ones who know how to “read” every footprint, rustle, and shadow.

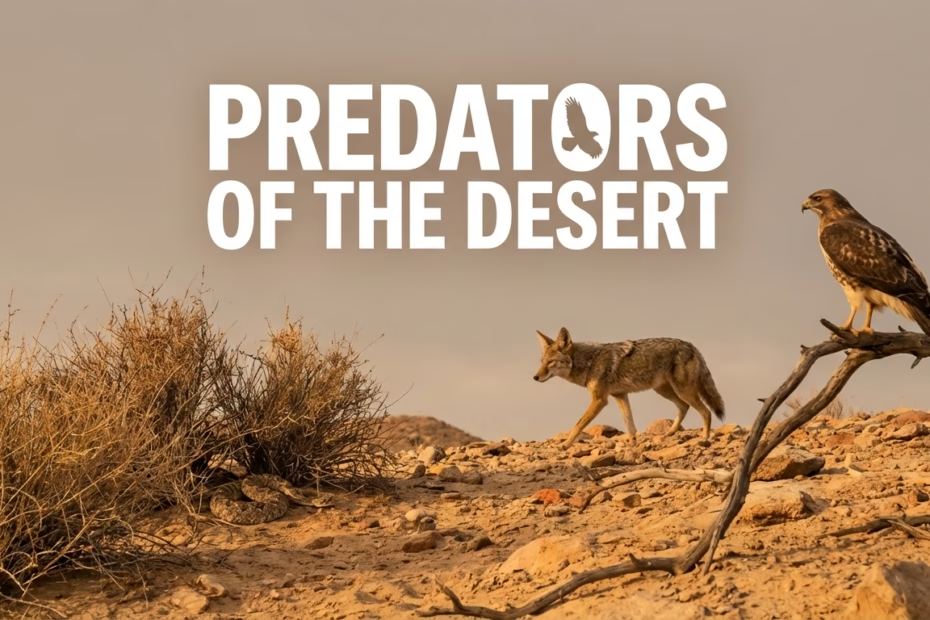

Predator Groups You’ll Meet Across The World’s Deserts

No single predator defines all deserts. Instead, you’ll see recurring roles filled by different species in different regions—Sahara, Sonoran, Namib, Atacama, Gobi, Thar, Kalahari, Great Victoria, and beyond. The names shift, the strategies rhyme. That’s the beauty of convergent adaptation: similar problems, similar solutions.

Mammalian Hunters

Desert mammals often look like they’re built for comfort, then you notice the details: long legs for distance, oversized ears for cooling and hearing, fur that insulates against heat and cold, and a lifestyle tuned to dusk and night. Many are generalists—they can shift from rodents to reptiles to insects when the menu changes. That flexibility is a survival superpower.

- Foxes and small canids (like fennec and kit foxes): light frames, big ears, clever foraging, and quick pounces.

- Wildcats (like sand cats and other desert-adapted cats): low profiles, excellent hearing, and short, explosive attacks.

- Coyotes and jackals in arid zones: adaptable diets, strong endurance, and smart route choices along washes and edges.

- Mustelids and mongooses in some regions: fearless, fast, and skilled at digging prey out of cover.

Birds Of Prey And Night Hunters

Desert air is often clear, and that favors hunters that can spot tiny movement from far away. Raptors use height as an advantage—cliffs, saguaros, acacia trees, even a lone dead snag. Owls rule the dark with silent flight and pinpoint hearing. In places with strong thermals, soaring becomes a low-cost way to search huge areas. It’s efficiency with wings—pure desert logic.

- Falcons: fast aerial pursuit, often along open plains where prey has fewer hiding places.

- Hawks and eagles: scanning from perches, then a controlled dive or glide to capture prey.

- Owls: nocturnal specialists that hunt by sound as much as sight.

- Corvids (ravens in many deserts): highly intelligent opportunists that can take small prey and also scavenge.

Reptiles That Hunt With Patience

Many desert reptiles run on a different clock. Their metabolism can be slow and steady, which means they can wait longer between meals. Snakes often rely on ambush and precise strikes, while lizards may combine stalking with short bursts. Some species are most active during cooler windows—early morning, late afternoon, or night—because heat management matters as much as hunting skill. You could call it timing as a weapon, minus the drama. Just smart biology.

- Desert vipers and rattlesnakes: ambush near trails, burrows, and rocks where prey funnels through.

- Sidewinding specialists: movement that reduces contact with hot sand and improves traction on loose slopes.

- Monitor lizards in some deserts: active foragers with strong senses and impressive stamina.

- Small gecko hunters: insect-focused predators with night vision and sticky-foot agility.

Arthropod Predators In The “Small But Mighty” Category

If you only look for big animals, you miss a huge part of desert predation. Arthropods—scorpions, spiders, solifuges, predatory beetles, antlions—are often the most numerous hunters in arid systems. They control insect populations, prey on small reptiles, and become food for larger predators. It’s a layered network, like stacked gears. Their adaptations can be wonderfully specific: vibration sensing, burrow traps, and chemistry-based defenses.

- Scorpions: nocturnal hunters that use touch and vibration cues in sand and gravel.

- Trap-building specialists (like antlions): waiting in sand funnels for insects to slip.

- Fast ground hunters (some spiders and solifuges): high-speed bursts and strong grip.

- Ambush beetles: quick grabs on passing insects, often near vegetation.

How Desert Predators Hunt When Every Calorie Counts

Long chases are expensive in heat and dryness, so many desert predators prefer plans that look almost lazy—until they work. The desert rewards short, decisive effort. Some hunters wait. Some sprint. Some dig. Some listen. Most do a mix, switching tactics with temperature, moonlight, wind, and prey behavior. That flexibility is the story. Always has been.

- Sit-And-Wait Ambush: hiding at burrow entrances, under shrubs, beside rocks, or along narrow trails where prey naturally passes.

- Short-Burst Pursuit: quick sprints that end fast—often used by foxes, some cats, and many lizards.

- Dig-And-Flush: excavating prey in burrows or pushing it into the open with coordinated movement.

- Aerial Strike: scanning from above, then a swift drop or glide to grab prey with talons.

- Venom-Or-Grip Subdual: using chemistry or a powerful bite to reduce struggling and save energy.

Senses That Beat Heat And Distance

Deserts are open, but they’re not quiet. Wind drags scent trails. Sand and gravel carry vibrations. Temperature changes create tiny “edges” where animals move and hunt. Predators exploit those edges with specialized senses. Some can detect heat differences; others can pinpoint rustles in the dark; many can smell a trail hours after it was made. It’s not magic—just tuned equipment and practice. Nature’s high-resolution sensors.

Heat Detection

Some snakes use facial pit organs to sense infrared warmth, helping them track prey even in low light. It’s temperature vision—a neat trick in a place where nights can get surprisingly cool. Warmth becomes a signal.

Sound Mapping

Owls and other night hunters use asymmetrical ear placement and facial discs to “map” sound. In practical terms, a tiny rustle under a shrub can be as obvious as a flashing light. That’s acoustic precision—quiet technology built into feathers and bone.

Scent And Chemical Clues

Many mammals track prey through scent trails that survive in cool nighttime air. Some reptiles combine tongue-flicking with specialized organs to read chemical traces. It’s an invisible map, and in deserts that map can be more reliable than sight. Smell becomes navigation.

Heat And Water: The Hidden Side Of Predation

Hunting is never just about prey. In deserts, it’s also about body temperature and hydration. That’s why so many predators are nocturnal or crepuscular. Shade isn’t just comfort; it’s a strategy. Burrows, rock crevices, and thick shrubs act like natural air-conditioning. You’ll see animals “time-slice” their day into safe windows, then rest hard. Work when it’s efficient, pause when it’s not.

- Water from food: many predators meet much of their moisture needs through prey tissues, especially when free water is rare.

- Cooling by behavior: resting in shade, using burrows, and limiting midday movement can save more water than any physiological trick.

- Heat-smart movement: some animals reduce contact with hot ground or move along cooler surfaces like rocks and vegetation patches.

- Seasonal switching: in cooler months, activity periods expand; in hotter months, activity becomes tightly scheduled.

A Simple Way To Think About Desert Hunting

Imagine you’re carrying a phone with a low battery and no charger. You don’t stream video all day—you pick the moments that matter. Desert predators do the same with energy and water. They invest in high-probability moves, then conserve. It’s discipline built into biology. Nothing wasted.

Predator Roles In The Desert Food Web

Desert predators aren’t lined up in a single neat chain. It’s more like a web with multiple “lanes” running at once: insects feeding lizards, lizards feeding snakes, rodents feeding owls, and carrion feeding scavengers. Many predators also compete, sometimes indirectly, by hunting the same prey at different times. That overlap creates stability. When one pathway weakens, another can carry the load. Redundancy is resilience, desert-style.

| Predator Type | Typical Hunting Window | Common Prey Targets | Signature Strategy | Desert Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Canids | Dusk, Night, Dawn | Rodents, Insects, Small Reptiles | Short-burst pounce, digging | Flexible diet |

| Wildcats | Night, Dawn | Rodents, Birds, Lizards | Stealth stalk, sudden grab | Low-profile ambush |

| Raptors | Day (cooler hours) | Rodents, Lizards, Small Birds | Perch-and-scan, aerial strike | Wide search range |

| Owls | Night | Rodents, Small Birds, Large Insects | Silent flight, sound targeting | Hunt in darkness |

| Snakes | Evening, Night, Dawn | Rodents, Lizards, Birds | Ambush and quick strike | Low energy use |

| Scorpions And Spiders | Night | Insects, Small Reptiles | Vibration-based capture | Micro-habitat mastery |

Seasonal Shifts: When The Desert Changes The Rules

Deserts can swing between “lean times” and sudden abundance. After rain, prey populations and insect activity can rise quickly, and predators respond with more movement and broader foraging. During dry stretches, predators may tighten their territories around reliable patches—vegetation edges, rocky shade lines, washes, and permanent water. You’ll often see a shift from specialization to opportunism. It’s not random; it’s a carefully tuned response to probability. Chasing certainty.

- After rainfall: more insects and plant growth can indirectly boost rodents and small reptiles, which supports more predator activity.

- During heat peaks: activity windows shrink; predators hunt more at night and rest more in protected shelters.

- In cooler seasons: daylight hunting can increase in many regions, especially for birds of prey.

- During windy periods: scent trails and sound cues change; some predators rely more on sight and ambush.

Predators As Desert Engineers

Even without building dams or felling trees, predators influence desert structure. Their dens and burrows can be reused by other animals. Their hunting pressure changes where prey feeds, which changes where plants get nibbled, which can shift the micro-landscape over time. And their leftovers feed scavengers and decomposers, enriching soil in tiny, important patches. This is the desert’s version of ecosystem engineering: subtle, persistent, and surprisingly powerful.

Burrows And Shelters

Burrows are “real estate” in deserts. When a predator digs or expands a den, other animals may later use that space for shade, nesting, or escape. A single shelter can support a small neighborhood of life. Habitat by accident.

Nutrient Hotspots

Desert soil can be thin, so nutrients matter. Predators concentrate nutrients through scat and leftovers, creating small fertile patches that can influence plant growth and insect activity. It’s a tiny spark that can ripple outward. Small inputs, big effects.

Behavior Shaping

Prey species don’t move randomly when predators are around. They change routes, feeding times, and shelter choices. Those patterns shape where grazing pressure lands and where seeds survive. Predators are like invisible fences—not physical, but very real. Landscape by fear-of-being-caught.

Places Where Desert Predators Thrive

Deserts are patchy, and predators love patches. If you map where hunters spend time, you’ll keep finding the same features: edges, funnels, and “resource anchors.” That could be a rocky ridge (shade and dens), a wash (travel corridor), sparse trees (perches), or a seasonal water source (prey magnet). The desert is huge, but predators focus on the useful geometry. It’s like knowing which streets in a city always have traffic. Same idea, different world.

- Wadis, washes, and dry riverbeds: natural highways for movement and hunting.

- Rock outcrops and talus slopes: shade, dens, and ambush cover.

- Vegetation islands: insects and small mammals cluster around plants.

- Dune edges: prey often travels along firmer margins and wind-shaped ridges.

- Cliffs and tall plants: perfect raptor perches for scanning wide areas.

Respectful Encounters With Desert Predators

Most of the time, desert predators want space, shade, and an easy route away—not attention. If you’re near predator habitat, a calm, respectful approach keeps wildlife behavior natural and reduces stress for animals. Keep it simple: observe, appreciate, and let them keep their routine. The desert already asks a lot of them. Give them room. Always.

- Watch from a distance and avoid surrounding or blocking movement paths.

- Do not feed wildlife; it changes natural hunting behavior and shifts food webs.

- Keep noise low, especially at dusk and night when many predators are active.

- Stay on durable surfaces where possible to reduce disturbance to burrows and micro-habitats.