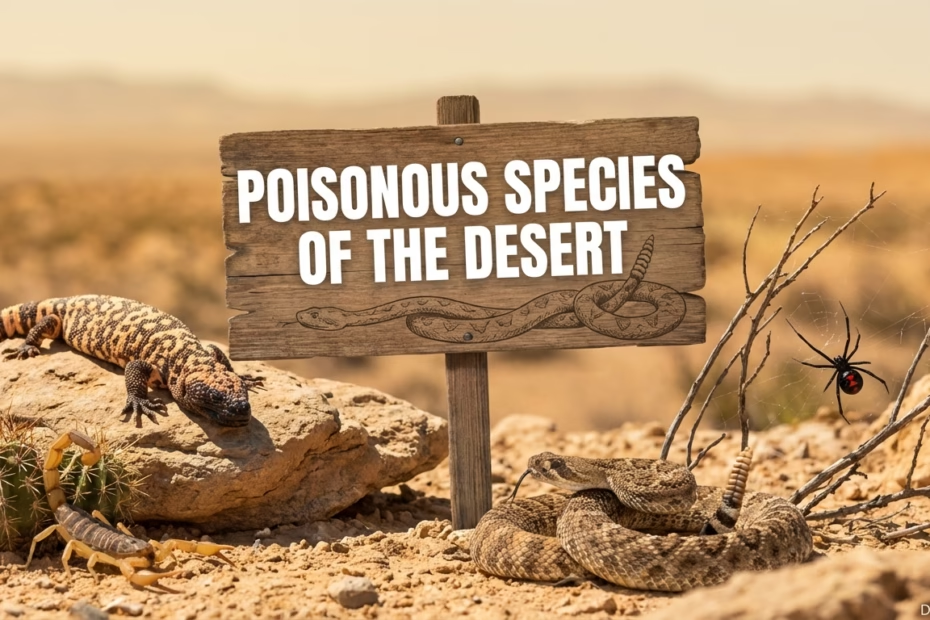

Deserts look quiet from a distance, yet they’re packed with organisms that survive by chemistry as much as by claws or roots. In places where water is scarce and shade is precious, a sting, a bite, or a bitter leaf can act like a fast “No, thanks” sign. This guide explores poisonous and venomous desert species with a clear focus: what they are, how their defenses work, and how people typically avoid problems while respecting desert life.

- What Poisonous Means in a Desert Context

- Why Chemical Defenses Show Up So Often in Deserts

- Venomous Desert Animals

- Scorpions

- Desert Snakes

- Widow Spiders and Other Desert Spiders

- Venomous Lizards in Arid Regions

- Stinging Insects and Venomous Myriapods

- Poisonous Desert Plants and Irritating Saps

- Datura and Thornapple

- Milkweeds and Cardiac Glycosides

- Castor Bean in Arid Landscaping

- Euphorbia Latex and Skin Irritation

- Practical Safety Around Desert Toxins

- Habits That Help

- When Exposure Happens

- How Desert Toxins Fit Into the Ecosystem

- Common Questions People Ask

- Are All Desert Scorpions Dangerous

- Is Venom the Same as Poison

- Why Do So Many Desert Plants Have Strong Sap

- Can You Identify Dangerous Species by Color Alone

What Poisonous Means in a Desert Context

People often say “poisonous” for anything that can hurt. In biology, the split is simple and useful. Venom is delivered by a sting, bite, or spine. Poison harms when it’s eaten, inhaled, or absorbed through sensitive tissue. A third category matters in deserts too: irritants, like caustic plant sap or defensive secretions that burn the eyes or mouth without being classic “poisons.”

| Type Of Defense | How It Gets Into The Body | Typical Desert Examples | Why It Helps In Dry Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Venom | Injected by sting/bite | Scorpions, rattlesnakes, widow spiders | Stops threats quickly; helps capture prey efficiently |

| Poison | Eaten or absorbed | Datura (thornapple), milkweeds, castor bean | Discourages grazing when plant regrowth is slow |

| Irritant | Touch or splash to eyes/mouth | Euphorbia latex, spiny plants with irritating sap | Creates instant discomfort; reduces repeated browsing |

Why Chemical Defenses Show Up So Often in Deserts

In deserts, energy is tight and mistakes are costly. A prey animal can’t always sprint far in hot sand, and a plant can’t easily replace leaves lost to hungry mouths. That’s where chemical defenses shine. Venoms and plant toxins act like concentrated bargaining chips: a small dose, a big message. Many desert species also live in open habitats, so a visible warning (bright bands, bold patterns, raised tails) paired with strong chemistry becomes a clean survival strategy.

Desert toxins are often about efficiency. They reduce long chases, repeated attacks, and wasted water.

Field Note

Venomous Desert Animals

Venom is best understood as a toolkit, not a single substance. Many venoms are mixtures of proteins and peptides that target nerves, blood chemistry, or muscle control. The same “type” of animal can have different venom profiles depending on species and region, so broad patterns matter more than trivia. The goal here is clear, accurate orientation, with practical awareness rather than fear.

Scorpions

Across hot deserts from the Sonoran and Mojave to the Sahara and Arabian deserts, scorpions are a classic example of venom for defense and hunting. Many medically significant species belong to the family Buthidae. Their venoms commonly contain neuroactive components that can interfere with nerve signaling, which is why a sting may cause intense localized pain and, in some cases, broader body symptoms. Most encounters happen when a scorpion is accidentally pressed against skin—inside shoes, under bedding, or beneath rocks.

- Where They Hide: Cool crevices, under stones, within wood piles, under loose bark, and sometimes in homes near desert edges.

- Why They Sting: Usually defensive contact, not pursuit.

- What People Notice: Pain, tingling, swelling; in more serious cases, symptoms may spread beyond the sting area.

- Helpful Habit: Shake out footwear and gloves before putting them on.

Desert Snakes

Desert snake venoms are often described by what they tend to affect: some lean toward tissue effects, some toward blood-related effects, and some include neuroactive components. In reality, many species carry blends, and effects can vary. Desert rattlesnakes in North America, horned vipers in North Africa, and saw-scaled vipers across parts of arid Asia are well-known venomous groups. The main pattern worth remembering is simple: venom is used for prey capture and defense, and most bites occur when a snake is surprised, cornered, or handled.

Common Desert Patterns

Heat drives schedules. Many species are most active at dawn, dusk, or night. In warm seasons, snakes may use roads and trails because they hold heat—the ground becomes a radiator. Watching where hands and feet go reduces surprises.

What Not To Rely On

Sound is not a guarantee. Some rattlesnakes may not rattle, and many venomous snakes worldwide don’t make warning sounds at all. Assume silence means nothing. Distance is the safest signal.

Widow Spiders and Other Desert Spiders

Several spider groups thrive in arid environments by keeping activity low during the hottest hours. Widow spiders (Latrodectus) are famous for neuroactive venom components and are often found in sheltered spots like wood piles, rock cavities, and outdoor storage areas. Most spider bites are defensive and relatively uncommon, usually happening when a hand slips into a hidden web space. The big takeaway is behavioral: avoid blind grabbing, especially around dark crevices.

- Typical Retreat Spots: Under ledges, inside stacked materials, around outdoor furniture, within storage corners.

- Why Bites Happen: Squeezing or pinning the spider against skin.

- Low-Drama Prevention: Use gloves when moving stored items; look before you reach.

Venomous Lizards in Arid Regions

Venomous lizards are rare globally, which makes desert examples especially interesting. The Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum) lives in arid landscapes of the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. It has venom glands and delivers venom through grooved teeth during a bite. Encounters are uncommon because these lizards spend substantial time sheltered, emerging during suitable temperatures. Here, respectful distance does the job—no theatrics needed. These animals are part of the desert’s balance.

Stinging Insects and Venomous Myriapods

Desert chemistry isn’t only about headline animals. Many deserts host stinging wasps, bees, and ants, plus large centipedes. Tarantula hawk wasps, harvester ants, and Scolopendra centipedes are all examples where the “weapon” is a sting or bite that can produce immediate pain and swelling. These species are typically not looking for trouble. They’re busy hunting, nesting, or moving through their microhabitat. The desert rule stays the same: don’t put skin where you can’t see, and treat nests like “no-entry zones.”

Poisonous Desert Plants and Irritating Saps

Desert plant toxins often target grazing animals, not people—but human exposure can happen through curiosity, foraging mistakes, or sap contact. Plant chemistry can be powerful even in small amounts, because a plant can’t run away. Think of it like a “locked door” made of molecules. The safest mindset is taste nothing you can’t identify with certainty, and keep plant sap away from eyes and mouth. Simple caution goes far.

Datura and Thornapple

Datura species grow in many warm, dry regions and are known for showy, trumpet-like flowers and spiny seed pods. They contain tropane alkaloids that can be hazardous if ingested. The risk is mostly from swallowing plant parts or seeds, especially by accident. In desert landscapes, datura may appear after rains, taking advantage of brief moisture windows like a plant that “wakes up fast” when the desert briefly softens.

Milkweeds and Cardiac Glycosides

Milkweeds (Asclepias) include desert-adapted species and are famous for milky latex sap. Many contain cardiac glycosides that can be toxic if eaten. For people, the most common issue is sap irritation on skin or sensitive tissues. For wildlife, the chemistry shapes feeding behavior—some insects specialize on milkweed, while many grazers avoid it. This is chemistry as an ecological boundary line.

Castor Bean in Arid Landscaping

Castor bean (Ricinus communis) can grow in hot, dry climates and is sometimes seen near settlements, waterways, or disturbed ground in arid regions. Its seeds contain compounds that are dangerous if swallowed. Because the plant is often associated with human-altered habitats, the best prevention is straightforward: don’t sample unknown seeds, and keep children and pets away from unfamiliar ornamentals. Curiosity is normal; swallowing is optional.

Euphorbia Latex and Skin Irritation

Many Euphorbia species (including succulent-looking forms in dry regions) produce a white latex sap that can irritate skin and is especially unpleasant in eyes or mouth. This is less about “poison” in the dramatic sense and more about a chemical burn-style deterrent. In desert gardens and wild areas alike, a simple habit helps: avoid breaking stems, and wash hands after plant contact. Protecting eyes is the priority.

| Plant Or Plant Group | Most Risky Parts | Common Exposure Route | What People Typically Experience | Easy Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Datura (thornapple) | Seeds, leaves | Accidental ingestion | Potentially serious body-wide effects | Do not taste unknown plants; supervise children |

| Milkweeds (Asclepias) | Latex sap, leaves | Sap contact; ingestion | Irritation; ingestion can be hazardous | Avoid sap contact; wash after handling |

| Castor Bean | Seeds | Ingestion | Can be hazardous if swallowed | Keep seeds out of reach; remove fallen seeds |

| Euphorbia | Latex sap | Touch; eye exposure | Strong irritation, especially to eyes | Gloves for pruning; keep sap away from face |

Practical Safety Around Desert Toxins

Most problems are preventable with calm habits. Think of deserts like a dark room: you don’t sprint barefoot; you turn on a light. Here, your “light” is attention. These steps keep people comfortable while letting wildlife do its job.

Habits That Help

- Look First: Check before reaching into cracks, rock piles, or stored gear.

- Shake and Tap: Footwear, gloves, and sleeping bags can hide small animals.

- Give Space: If an animal is noticed, step back and let it move away.

- Wear Barriers: Closed shoes in rocky terrain reduce surprise contact.

- Keep it simple: Most safety is about avoiding accidental pressure on a hidden creature.

When Exposure Happens

- Stay Calm: Panic increases risk of falls and missed details.

- Seek Professional Care if symptoms are spreading, intense, or worrying.

- Avoid Home Experiments: Do not try to “test” plants or handle wildlife.

- Note the Context: If safe, remember the animal’s general look and location for responders.

How Desert Toxins Fit Into the Ecosystem

It’s easy to treat venom and poison as “weapons,” yet in ecology they’re also traffic signals. They shape who eats whom, who avoids whom, and where animals choose to live. Venomous predators can control insect and rodent populations, which can influence vegetation patterns over time. Poisonous plants can steer grazing pressure toward hardier species, protecting fragile seedlings during short growing windows. In deserts, where every rain event matters, these chemical relationships help stabilize the whole system. Chemistry becomes a kind of invisible architecture.

Common Questions People Ask

Are All Desert Scorpions Dangerous

No. Many scorpions can sting, yet only a smaller portion are associated with more serious medical outcomes. The safer assumption is to treat any scorpion as capable of delivering a painful sting, keep distance, and avoid accidental contact. Respect beats guessing.

Is Venom the Same as Poison

They’re different delivery systems. Venom is injected; poison typically works when eaten or absorbed. That distinction matters because prevention differs: watch where you place hands and feet for venomous animals, and avoid tasting unknown plants or seeds for poisonous species. Same desert, different rules.

Why Do So Many Desert Plants Have Strong Sap

In arid climates, plants often can’t quickly replace lost tissue. Defensive sap and bitter compounds reduce repeated browsing. It’s like putting a natural lock on a slow-growing resource. Less damage today means survival tomorrow.

Can You Identify Dangerous Species by Color Alone

Color can hint at warning signals in some animals, yet it’s not a reliable filter. Many harmless species mimic bold patterns, and many medically significant species are camouflaged. The most reliable approach is behavioral: don’t handle wildlife, and avoid blind contact with crevices and clutter. Distance is the universal identification tool.